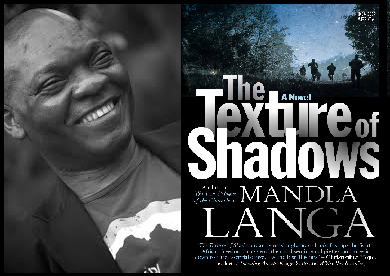

Mandla Langa is an accomplished author whose book The Lost Colours of the Chameleon won the 2009 Commonwealth Writers’ Best Book Award for Africa., and his latest novel is The Texture of Shadows. Mandla speaks to us about growing up reading in a world where books were not a priority:

I grew up in Mayville, Durban, as the fifth child in a family of nine, including my parents. In the late fifties, Mayville was a suburb where Africans, whites , Indians and coloureds lived in harmony. One of my earliest memories was of Mrs Parboo, our neighbour, coming to our house carrying a pot of curry she had cooked.

I was surrounded by books. My father was a minister of religion and his favourite book was the Bible and my mother, who was always around, was also our teacher of sorts. She traced for us the outline of the pictures in books, for instance, in the encyclopaedias, and explained the meanings of the accompanying text.

"It was my father’s stories...which stoked up a hunger within me to

make a connection with what was being said and the written word"

My brothers were already big. Every time they returned from school or work they would pore over a newspaper. I didn’t know the role played by a newspaper in our lives but had an idea that this thing called “news” was important. But I could not understand how they could collect and make sense of a bunch of symbols scattered along a page and then “speak” out what they stood for.

It was in “speaking” out the power of those symbols that I learnt of the government. The government was also called uHulumeni. I imagined him as a big and tall white man from Pretoria where everyone wore a hat and spoke English through their nostrils. I always wondered if this Hulumeni had a wife and children and thought, even though he might have been rich and drove a big Oldsmobile, I would have had a pretty miserable childhood if he had been my father.

I liked cartoons. Mickey Mouse, Li’l Abner and Tumbleweeds and followed without understanding, thereby reinterpreting for myself the goings-on of the Heart of Juliet Jones and the brave boxing exploits of Big Ben Bolt.

"Nothing empowers a child more than the ability to read independently"

But it was my father’s stories, of his travels with my mother in a Southern Africa that had no borders, which stoked up a hunger within me to make a connection with what was being said and the written word. The code was broken one day when my father walked with me to the little shopping centre called Rana’s.

On the way we passed a sign: BEWARE OF THE DOG. I asked him what it meant and he pointed at the dog – some mingy mutt that wouldn’t have harmed a fly – and said it meant that I should be aware of the dog.

“Does ‘beware’ mean ‘be aware’?” I asked, the penny dropping.

“Yes,” he said. He smiled down at me, excited at the revelation unfolding before us. He was, after all, a man of the cloth.

From that day onward, I scoured and scanned anything written down, looking and deciphering the code of words and the meaning behind them.

I forgot the stylised cartoons and comics for a while, looking, instead at the words, mesmerised by their sound. Of course all this meant that, when I started going to school, doing Sub-standard A, the first step for an African child in the days when apartheid held sway, the teachers had a hard time trying to undo what my father had taught me.

Nothing empowers a child more than the ability to read independently.