As part of their package of support to Early Childhood Development centres, Nal’ibali Literacy Mentors recently explored the power of Storyplay – a strategy using imaginative (pretend) play as a way to support young children’s exploration and understanding of stories, people and the world around them. Following a week of training with Storyplay consultant Sara Robinson, this is what we learnt:

A factor that characterises human societies is that we are able to understand each other’s mental states. Scientists call this Theory of Mind – we can comprehend that other people have beliefs, feelings and experiences that are different to our own. Infants from 7 to 9 months old begin to acknowledge and track what their parents take notice of and react to. As babies grow, their understanding of others’ emotions deepen over time until they become adults with one very important characteristic – empathy. The ultimate human trait.

Empathy, being able to imagine and care about how it feels to be someone else, is something that develops gradually as we mature – and the way it happens and the kind of empathy we develop depends a lot on our experiences as a child. Every person you speak to, every story you hear or book you read and every lesson you learn comes together to contribute to the person you are becoming. More than that, who we are depends largely on the ability to be self-reflective and understand the weight of one’s own words and actions on others.

So does literature make us more empathetic and understanding human beings?

Yes, it does. Sharing stories with children can be a powerful force to get them to engage with a character’s life and emotions, cultivating empathy. This is one of the important reasons why a Storyplay approach is so appropriate for young children.

But it also depends on the way you connect with a story. Young children tend to understand the world via their parents or caregivers. Children look to you to be able to work out the meaning of most things in life. This is true for reading too. By sharing a story with your children, you get to see the narrative through their eyes – you notice what message they take from it, and how they understand the characters. This sharing puts you in a particularly powerful position to be able to analyse and reflect on the story with them. You can ask questions and add insights that may not have immediately occurred to them. Essentially, you act as children’s moral compass in their experience of the tale.

Does language affect children’s understanding of their reality?

Absolutely – and not just kids, adults too. Even before babies fully understand the meaning of words and sentences, they learn to love the sound of language. As they grow older, their language and how they learn to express themselves becomes integrated into the way they understand reality.

We’re all narrators and storytellers of our own lives. We learn from childhood how to describe ourselves and what happens in our lives. Moreover, we deal with emotions like joy, envy, pain and sadness using language and stories.

How to put Storyplay into action

Young children – from 3 to 6 years – have boundless imagination and spend much happy and productive time in their make-believe worlds. In fact, storytelling and reading, play, talking and singing are shown to be crucial for language and concept development in the earliest years of life. And because young children learn effortlessly through stories and play, Nal'ibali offers an approach to support this.

As well as reading a story during a Storyplay session, children enter and create the story’s world through their play. Without the limitations of a strict script, they’re each given a character in the tale to embody. This gives them the opportunity to understand and interpret the character however they please. Drawing and writing (real or pretend!) is also done by adults and children, to enhance the exploration of the story and what it means for everyone involved.

Last week our own team of mentors spent a lively training session in Storyplay with consultant Sara Stanley and Ntombizanele Mahobe from PRAESA. One of the stories they read was The Pied Piper. Each person was given a character to play and invited to act out the tale in the best way they understood it. What ensued was an engaging and interactive Storyplay, followed by a discussion of why each person acted the character in the way that they did.

Our Storyplay training shows why it’s important to get children to connect emotionally with many different stories. They are in the process of discovering their own moral compass and their own references for understanding the world. Adults’ active engagement and interaction with them is the piece in the puzzle that helps to enrich this process as they work to create their own meaning and narratives.

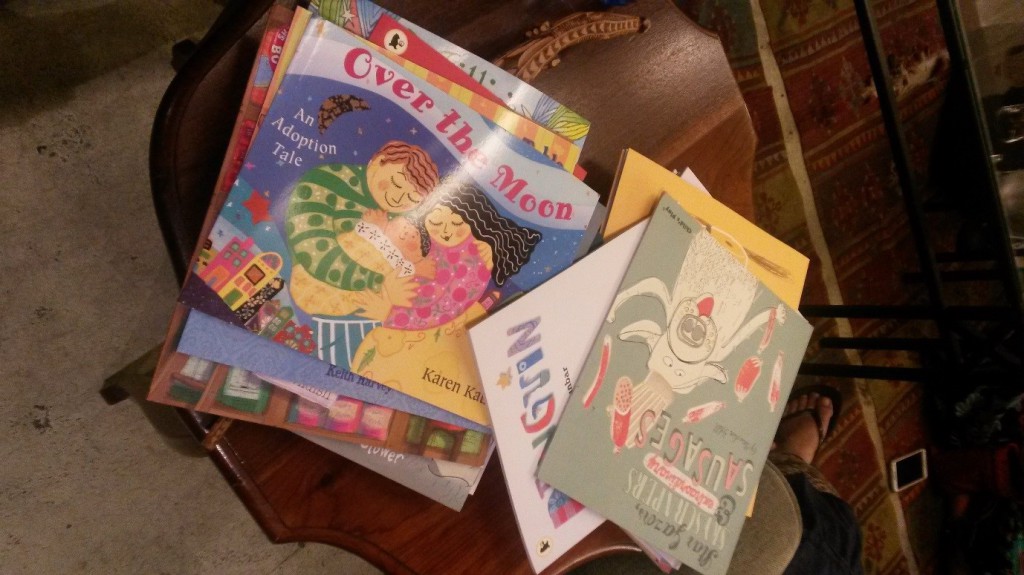

Nal’ibali Literacy Mentors discussed how books and stories that inadvertently teach children how to ‘put themselves in someone else’s shoes’ and express their feelings are building blocks in their future interactions. Some of our mentors’ favourite books include those with a deeper meaning behind the colourful pastels:

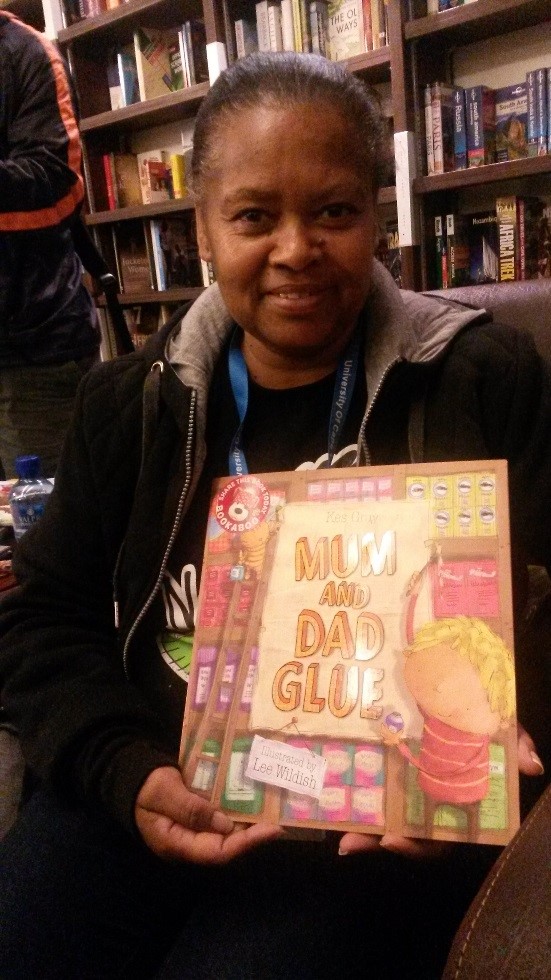

Mum and Dad Glue

Marilyn Cupido, Free State Literacy Mentor, chose the book Mum and Dad Glue by Kes Gray – an emotive little story about a child hoping to keep his parents from an imminent divorce. She found that this book approached this common topic in a tender and sensitive way – which, for her, is a useful tool to open dialogue with young kids who have separated parents.

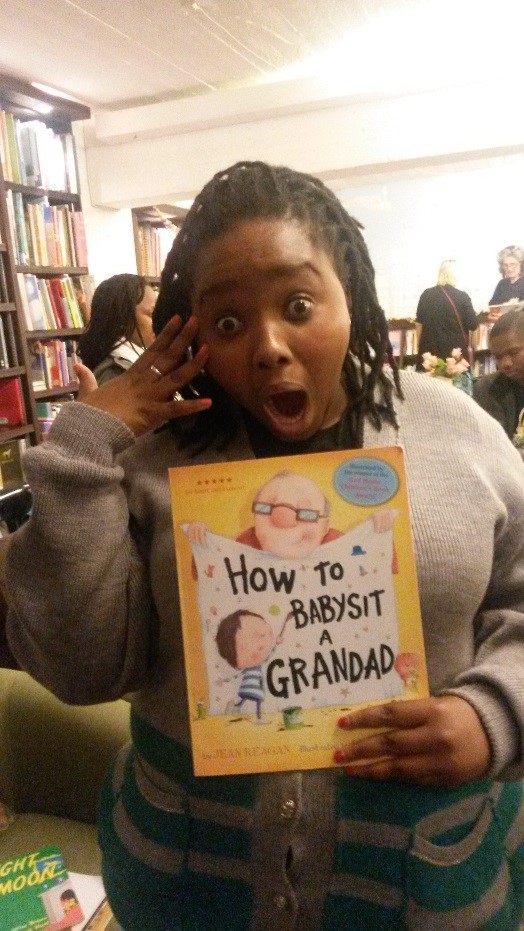

How to Babysit Grandad

Rinae Sikhware, our Limpopo Mentor, picked a book called How to Babysit Grandad by Jean Reagan. Her reasons for choosing this story centred on the loss of her own grandfather. She immediately connected with the story and felt it would be a lighthearted read to show children how they’re not so different from their grandparents.

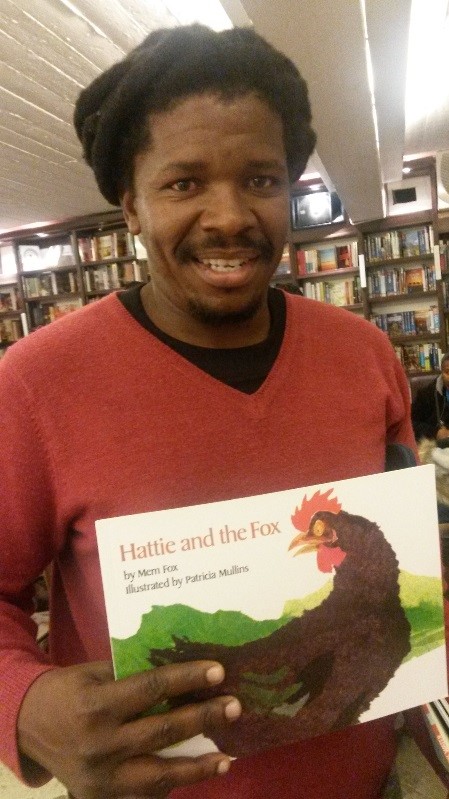

Hattie and the Fox

The story of Hattie and the Fox by Mem Fox resonated with Bongani Godide, our Literacy Mentor from Gauteng, because it reminded him of the tales he used to hear growing up. Bongani feels that culture and tradition is important when picking out books for children to read. His sense is that the more it resonates with their heritage and culture, the better kids will be able to connect with the story.