One of my favourite storybook characters as a child was Mrs Tiggywinkle from The Tale of Mrs Tiggywinkle by Beatrix Potter. She was a hedgehog who miraculously reinvented herself daily – without ever compromising her true identity – into an industrious entrepreneur who ran a laundry service! There she was bustling across the rolling green hills of the English countryside, a world that for me existed only in storybooks, the conversations of my parents and birthday cards from relatives. I was a South African English-speaking child steeped in a world of unearned privilege that included access to a wide range of storybooks in my home language.

I cannot imagine my childhood without the storybooks on my bookshelf and those I carefully selected each week from our well-stocked local library. Of course, I loved the stories that my parents told me to pass the time on a train journey or to get me to eat my supper but it is cuddling up with my dad and a book at bedtime – a ritual that lasted until I was 10 or 11 years old – that remains most deeply etched in my memory. Storybooks also inspired many hours of fantasy play where my friends and I became the characters we read about and were instantly transported to different places and times. In fact, it would be fair to say that most of my preschool years were spent lost in a storybook, one way or another.

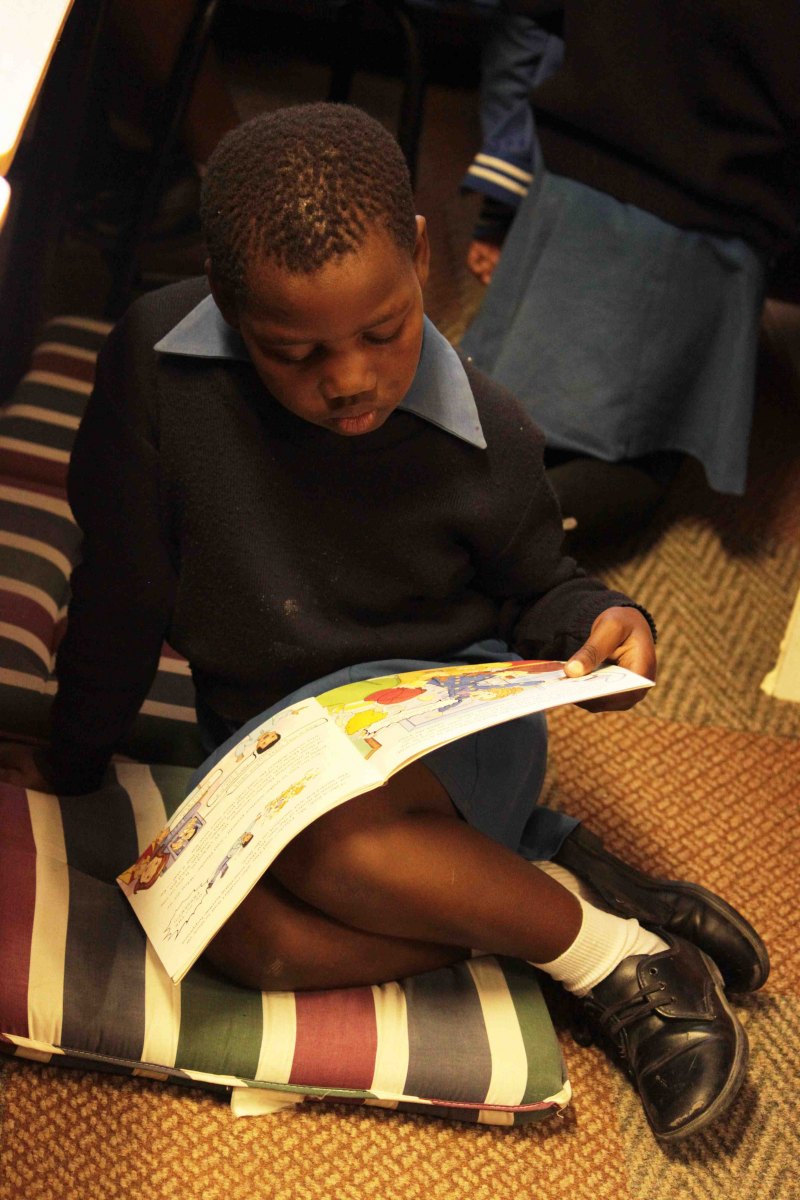

So then, what of the children who did not and, still today, do not have access to early experiences of picture books in the languages they use at home? Appropriately in South Africa, we are often reminded about our appallingly low literacy levels and how, for the majority of our children, books are things you only encounter at school. Every now and then as a response to this, we put vast amounts of time and energy (not to mention, money!) into reconstructing school curricula to ensure that children spend even more time learning the mechanical skills of reading, like sounding out letters and making sure that they have access to ‘readers’. So, what kinds of books are these ‘readers’ because if they are the only books that some children encounter, they need to be the very best children’s literature on offer otherwise there is little chance children will get ‘switched on’ to reading? Are they books that entertain children, immerse them in the richness of their language, inspire their imaginations and allow them to dream big for themselves? Unfortunately, they are not. Those books are mostly still the privy of children who are lucky enough to speak English or Afrikaans at home.

And so what about those parents who use languages other than English and Afrikaans at home and who read to their young children? If they want to buy storybooks or borrow them from the library, within weeks they would have exhausted the entire supply of books available in their languages. How can it be that in South Africa in 2012, we have a wealth of wonderfully rich storybooks and novels published for young children who are English- and Afrikaans-speaking but have an excruciatingly small selection for children who speak other languages?

When children see and read their languages represented in the storybooks they choose to read for enjoyment (or choose to have read to them), it affirms for them that their languages are important enough for people to write and publish in and the books provide a demonstration of what their languages can be used for. What then does it mean to a child’s developing sense of self (to which language is essential) to have to read and be read to in a language that is someone else’s?

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (to which South Africa is a signatory) asserts that all children have the right to develop to their fullest and to participate fully in cultural and social life. Reading enables children to contextualise their experience of the world against the backdrop of that of others. It has the potential to connect them to others and to help them build a sense of who they are and who they might become. In other words, it has a critical role to play in children’s developing sense of identity.

It is common knowledge that building a better society requires the affirmation of all children and giving them equal access to opportunity. Part of doing this has to be paying serious attention to ensuring that we are developing a quality children’s literature in all of our country’s official languages. This is not something that happens overnight and without investing significant resources. It requires people in positions of authority to roll up their sleeves and help create a landscape that enables children’s literature in all our languages to flourish in the long term. It requires a wide base of skilled and talented writers, illustrators, translators and publishers who think and act creatively with the intention of connecting with and inspiring children. Unfortunately, unless we begin to make good on our commitment to all South Africa’s children we’ll be saying these same things in another 10 years time.

Arabella Koopman is a Multilingual Materials Development Specialist at PRAESA. Before joining PRAESA, she worked in the publishing industry and as a teacher and teacher-educator. She has a special interest in developing and researching materials that support and extend children’s literacy in multilingual settings.

This editorial was originally published in the Sunday Times, 4 November 2012.